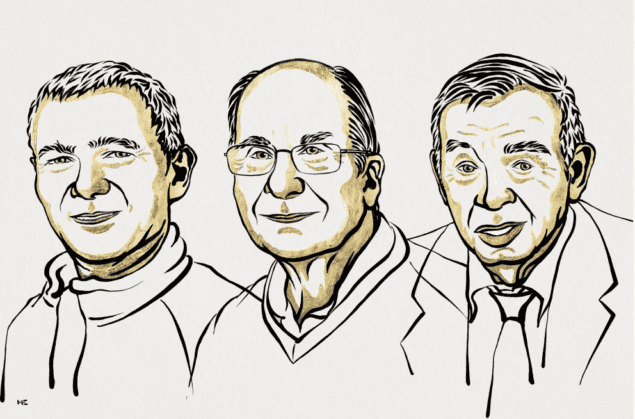

The Nobel Prize for Chemistry has been won by Moungi Bawendi, Louis Brus and Alexei Ekimov for “the discovery and synthesis of quantum dots”.

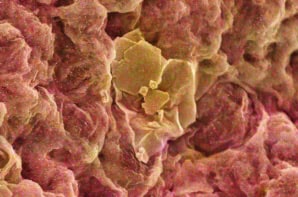

Quantum dots are extremely small particles just a few atoms in size and their properties allow them to emit light at specific wavelengths. Since the 1930s physicists had known that, in theory, quantum effects could arise in nanoparticles that would give them unusual characteristics, but for decades it was difficult to create such materials in the laboratory.

That changed in the early 1980s, when Ekimov, who had a background in semiconductors, succeeded in creating size-dependent quantum effects in coloured glass.

The colour came from nanoparticles of copper chloride and he experimented with molten glass heated to a range of temperatures and with varied heating times. Once the glass had cooled he X-rayed it and found tiny crystals of copper chloride had formed inside the glass, with the manufacturing process affecting the size of the particles.

This was the first time that someone had succeeded to deliberately produce quantum dots with Ekimov demonstrating that the particle size affected the colour of the glass via quantum effects.

A few years later, Brus proved size-dependent quantum effects in cadmium sulphide particles floating freely in a fluid, finding that smaller particles had an absorption that shifted towards blue.

In 1993 Bawendi revolutionized the production of cadmium selenide quantum dots, resulting in controlling the temperature of a solvent to grow nanocrystals to a specific size and with a smooth and even surface. This development was necessary for them to be used in a range of applications, and they have since been used in computer monitors and television screens based on QLED technology.

From chemistry to physics

Bawendi was born in 1961 in Paris. He received his PhD from the University of Chicago in 1988 and did postdoctoral work at AT&T Bell Labs. He joined Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1990 where he has remained since.

Brus was born in 1943 in the US. He did a PhD in chemical physics from Columbia University in 1969. He then went to the US Naval Research Laboratory before moving to AT&T Bell Labs in 1973 until 1996. He then took a position at Columbia University where he remained for the rest of his career.

Ekimov was born in 1945 in the former Soviet Union. He received his PhD in physics in 1974 at the Ioffe Physical-Technical Institute, Russia. He then worked at the at the Vavilov State Optical Institute, Russia, and in 1999 became chief scientist at US-based Nanocrystals Technology Inc.

Early morning call

Bawendi spoke from the US during the press conference that followed the announcement of the award in Stockholm. He told Hans Ellegren “Don’t be sorry” for waking him up very early in the morning. Ellegren is secretary general of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and has the task of telephoning winners with the good news.

“It is quite an honour. [I am] very surprised, sleepy, shocked and very honoured,” said Bawendi. He added, “[Quantum dots] is a field with a lot of people that have contributed to it from the beginning, so no, I didn’t think I would get this prize. We’re all working together. I didn’t think I would get it.”

Also at the press conference was Heiner Linke, who is professor of nanophysics at Sweden’s Lund University. When asked whether quantum dots are physics or chemistry, he replied: “There’s a root of this field in semiconductor physics.” However, he pointed out that this prize focuses on the production and purification of quantum dots, adding “the methods of doing this come from chemistry”.

Quantum dots are famous for producing a wide range of vibrant colours, so it is not surprising that that the first applications have been in lighting and displays. Quantum dots have been used to adjust the colour of LED lighting from a cold white to warmer tones. Green and red quantum dots have been used in conjunction with blue LEDs to create computer and television screens.

Quantum dots are also finding use in biochemistry and medicine. They can be attached to biomolecules, for example, and the light they emit used to map out biological structures.

Winners leaked

At the press conference, Ellegren was questioned by several journalists about the leak of the winners’ names, which occurred several hours before the official announcement was made. This leak came as a great surprise to Nobel watchers because of the high level of secrecy that normally surrounds the decision process.

“We deeply regret that this happened,” said Ellegren, who added that the final decision about this year’s winners had not been made when the leak occurred. “The decision about the prize is not taken until the academy has met, and the academy met this morning.”

Ellegren was also asked whether it would be appropriate for Ekimov, who was born in Russia, to be invited to the Nobel prize ceremony in Stockholm on 10 December in light of the ongoing war in Ukraine. Ellegren said that decision rested with the Nobel Foundation (of which Ellegren is a director) and that the decisions about who wins Nobel prizes are based solely on scientific merit. “Alfred Nobel said that the most worthy person should receive the prize, regardless of nationality,” he stressed.

Physics World‘s Nobel prize coverage is supported by Oxford Instruments Nanoscience, a leading supplier of research tools for the development of quantum technologies, advanced materials and nanoscale devices. Visit nanoscience.oxinst.com to find out more.