Postage stamps are not just tokens we use to send letters – they also form part of our social history. Ian Briggs looks at how developments in nuclear physics have been depicted in postage stamps

In December 1942 US president Franklin D Roosevelt signed the Manhattan Project into existence. A scientific endeavour that culminated in the dropping of the Little Boy and Fat Man bombs three years later, the project was – for better or worse – the most significant development in the long history of nuclear physics. What is perhaps surprising, though, is that this pioneering field of discovery is captured forever through the medium of postage stamps.

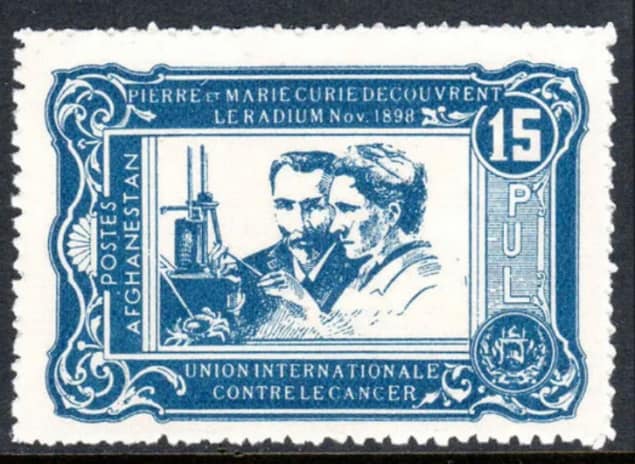

Marie Curie has appeared on more than 600 postage stamps and holds the record as the physicist with the most stamps ever issued in their name

Our story begins with Marie Curie, who shared the 1903 Nobel Prize for Physics with Pierre Curie for their studies of radioactivity. This phenomenon had been discovered in 1896 by Henri Becquerel, who won the other half of that year’s prize, but it is Marie Curie who is easily the most famous of the three scientists. She has appeared on more than 600 postage stamps and therefore holds the record as the physicist with the most stamps ever issued in their name. My favourite is the 1938 Afghanistan 15 pul stamp, which is the only one featuring Curie with her electrometer and was also the first stamp to depict a female scientist.

Curing the Curie complex

From her lab in Paris, Curie famously studied the radiation emitted by pitchblende – a glowing mix of uranium oxide and lead, which hailed from the Jáchymov mine in Bohemia, now part of Czechia. Known for its production of silver, the ore was delivered to Curie, who also used it to discover the elements polonium and radium. The mine’s fame as the birthplace of nuclear science was commemorated by the former Czechoslovakia in 1966 with a 60 haléř stamp (click here to view).

Ernest Rutherford – the New-Zealand-born physicist who discovered the atomic nucleus – is also commemorated on several stamps. One I particularly like was issued by New Zealand in 1971 to commemorate the centenary of his birth. The 1 cent stamp of the set includes a portrait of Rutherford along with a diagram of the Rutherford atomic model, which – correctly – envisaged electrons surrounding a dense central nucleus. The stamp nicely shows alpha particles being scattered back from the nucleus – the famous “gold-foil” experiment found in every school physics syllabus.

Rutherford could – and perhaps should – have won a Nobel prize for his discovery of the nucleus but he of course won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1908 for his work on the decay of radium. The Nobel committee obviously viewed radioactivity as chemistry, not physics, prompting Rutherford to famously remark that he had dealt with many different transformations, but that the quickest was his “own transformation in one moment from a physicist to a chemist”. Be that as it may, winning a Nobel prize is a sure-fire way to philatelic fame.

The Danish physicist Niels Bohr – who won the 1922 Nobel Prize for Physics for his work on the structure of atoms – has appeared on several Swedish stamps but my favourite is actually a Greenland 1963 issue, celebrating 50 years of “Bohr theory”, which describes how electrons exist in discrete orbits and can jump between them. I like this stamp because rather than containing just a visual portrait of the scientist, as was the trend until then, it also depicts Bohr’s work in the form of an equation (hν = E2–E1) and a diagram of orbiting electrons.

As the 1920s turned into the 1930s, the pace of research in nuclear physics picked up. In 1932 James Chadwick discovered the neutron. In 1938 Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassman, along with Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch (working under Bohr), discovered atomic fission. In 1939 Frédéric Joliot-Curie, Enrico Fermi and Leo Szilard confirmed the chain reaction experimentally. The final pieces of the bomb jigsaw were provided by Francis Perrin, who calculated the critical mass of uranium needed for a self-sustaining reaction, along with further work from Rudolf Peierls in Birmingham, UK.

Images on postage stamps are a great reminder of the role of science in the world around us and yet, they can also entrench inequities

Discovery in science is a bit like a self-sustaining reaction, in which new ideas are built on old ones and researchers stand on the shoulders of the giants who went before. Images of postage stamps are a great reminder of the role of science in the world around us and yet, they can also entrench inequities. The beautiful 60 pfennig German stamp first issued in 1979 (click here to view), for example, shows the splitting of a uranium nucleus but it mentions only Hahn, who was awarded the 1944 Nobel Prize for Chemistry. His co-discoverers – Meitner, Strassman and Frisch – who were left empty-handed are, once again, omitted from history.

Stamps don’t just reflect history but can shape it too.