Are spaceports the missing link needed to catalyse the UK space industry, or are they a can of worms best left to established spacefaring nations? Benjamin Skuse investigates

When you think of space launches, you probably imagine a NASA or SpaceX mission control, with rows of staff huddled over monitors, huge wall-sized screens, and loud celebrations when some tremendous rocket defies gravity to slice through the atmosphere and reach space.

You likely don’t think of a jumbo jet taking off from an unassuming regional airport in the seaside town of Newquay, tucked away in the south-west of England. But this was how, on Monday 9 January 2023, the UK attempted to join the growing number of countries launching rockets into space from their own soil. Run by Spaceport Cornwall – a consortium of Cornwall Council, Goonhilly Earth Station, the UK Space Agency and the launch operator Virgin Orbit – the “Start Me Up” mission aimed to put nine small satellites into low orbit, making it the first satellite launch from UK soil.

Rather than a rocket blasting off from a stationary, vertical position on the ground, Start Me Up used Virgin Orbit’s LauncherOne – a 31-tonne rocket that launches from under the left wing of a modified Boeing 747-400, called Cosmic Girl, while in flight. The event was bidding to be the fifth successful flight of the air-launched rocket.

With the mission’s eponymous Rolling Stones song playing to the gathered crowds, Cosmic Girl’s take-off from Cornwall was uneventful. The jumbo jet then flew to a “drop zone” roughly 10,500 m above the Atlantic, off the south-western tip of Ireland, where it released LauncherOne. Seconds later, the rocket’s first-stage NewtonThree engine fired, propelling it up to nearly 13,000 km/h. About three minutes later, the second-stage NewtonFour engine ignited, all seemingly going according to plan.

However, nearly two hours after take-off – just as Cosmic Girl was returning to land safely at Newquay – Virgin Orbit’s Christopher Relf announced on a live stream of the event: “It appears that LauncherOne has suffered an anomaly which will prevent us from making orbit for this mission.” LauncherOne did successfully reach space, soaring to an altitude of 180 km, but failed to orbit. The rocket and its payload of nine small satellites fell back to Earth. Some of them burned up on re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere, while the rest landed in a pre-approved section of the Atlantic Ocean.

Industry undeterred

The Start Me Up mission could be viewed as a cautionary tale for Virgin Orbit and other launch companies hoping to send rockets into space from UK spaceports. But if anything, it has galvanized those in the industry. Now that the crowds have dispersed, Melissa Thorpe, head of Spaceport Cornwall, has had time to rally for round two. “Of course, it was disappointing,” she says, “but at the same time we’re really excited that we kind of proved that capability and we’re moving forward, looking towards the next launch later this year.”

Also aiming for launches this year – conventional vertical ones in these cases – are two Scottish facilities: the SaxaVord spaceport on the island of Unst in Shetland, and Space Hub Sutherland at the A’Mhoine peninsula in Sutherland. Along with four more spaceports in the works, the UK’s space launch capability is certainly set to soar. For Ian Annett, deputy chief executive of the UK Space Agency, this is now a watershed moment for the UK space industry, which is already worth £16.5 billion a year to the country’s economy and employs nearly 50,000 people.

He argues that the UK is good at designing and building satellites, has attractive conditions for setting up operations centres, and has world-leading capabilities in exploiting space-based data. “The one thing that’s missing is launch capability,” he says. “If you can provide that end-to-end spectrum, it serves the broader endeavour so that we can do everything.”

Up to now, UK satellites have launched primarily from the US, French Guiana or Kazakhstan. But shipping satellites abroad is expensive for UK space businesses and it’s always risky transporting fragile cargo to distant sites. Domestic launch capacity offers a cheaper and safer alternative.

More broadly, the official line from the government is that space launch facilities will be a boon to the UK economy, swelling UK industry capitalization from £17 billion now to £40 billion by 2030. In turn, this growth will attract investment, provide new high-skilled job opportunities and encourage young people to study science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) subjects in preparation for careers in the space industry. But are these ambitions realistic?

One hurdle is competition. There are around 168 launch companies around the world, at different stages of development, vying for satellite developers’ business. “Probably about 50% of them only exist on PowerPoint,” says Annett. “I would predict that a large number will either consolidate or they won’t get off paper – so don’t believe everything you read about the number of launch operators.” Nevertheless, even if many fall by the wayside the launch market will inevitably become crowded, making it a challenge for UK spaceports to compete.

But Annett sees other advantages. “If you look at successful spaceports, they have generated other space-related activities around them,” he explains, pointing to Rocket Lab’s Launch Complex 1 in New Zealand where commercial deployments of smallsats have seeded an entire successful space industry in the country. Then there’s Houston Spaceport in the US, which has managed to attract a multitude of aerospace companies without ever hosting a launch or landing. “While many will conduct their business plans on how many launches they get a year and who their customers are,” Annett adds, “the real success factors will be defined by creating a centre of gravity for space-related activity.”

Spaceport Cornwall is already focused on this, looking beyond launch to ensure it survives and thrives. “For us, it’s about that wider cluster,” says Thorpe. “We want a sustainable business model that’s based on lots of different businesses using the site – being attracted here because of launch, of course – and then we just grow it organically.”

Space skills gap

Another challenge for the UK launch industry mirrors that of the country’s wider space sector: a yawning skills gap. Already 51% of UK space businesses worry about filling vacancies, with most of these roles focused on science, engineering or technical tasks. For example, the shortage of propulsion engineers in the UK has become so chronic that Annett says that the UK Space Agency is planning to sponsor PhD students to do propulsion subjects.

Joseph Dudley, director and founder of the thinktank Space Skills Alliance, sees a range of factors contributing to this shortage. “The space sector is growing very fast so obviously there’s more and more demand for people with the kinds of skills that space companies need,” he says. “But that’s in the wider context of there being quite a lot of competition with other STEM sectors that are also growing quite fast.”

These other sectors include finance and technology, where the major players are household names with deep pockets, attracting STEM talent from a young age through fun coding camps. They also have generous graduate schemes, recruit across all STEM disciplines, and offer attractive alternative education pathways for those who don’t attend university.

In contrast, the UK space sector is less flush with cash and follows more traditional recruitment practices, with 75% of workers holding at least one degree, usually in a physics or engineering discipline. “If I say ‘you’re going to need to do a four-year aerospace engineering degree’, that’s a hell of a commitment, it’s very expensive, and it means the sector is always drawing from a small pool of talent,” adds Dudley. Coupled with the UK space industry being dominated by start-ups with little capacity to train up recent graduates, it means there are simply not enough experienced people to go around.

For Dudley, plugging the skills gap calls for a multi-pronged approach. He believes the UK needs to explore some of the recruitment innovation seen in the tech sector to attract talent, and provide more training opportunities for young people. A bigger focus on recruiting and retaining women and people from other under represented groups is important too, along with making job adverts more attractive to job seekers in general. But for any of these aims to be met, people need to know that UK space careers exist and could be a viable and successful option for them, and this is where spaceports can play a key role.

Spaceport Cornwall is trying to inspire the next generation of space professionals by engaging with every single school in Cornwall through online and in-person programmes. It has also worked with Truro and Penwith College to co-develop the world’s first undergraduate-level Higher National Certificates and Diplomas (HNC/Ds) in space technologies. And the team has collaborated with the University of Exeter and Falmouth University on various educational projects. “Launch is almost a nice cherry on top,” says Thorpe. “As long as we’re out engaging with young people and inspiring them, that’s success to us.”

Is space still cool?

For many invested in the UK space industry, the logic goes that if young people see launches and space activity happening at UK spaceports, have interactions with members of the industry and can see viable career paths, then the sector can latch on to the “cool factor” that space has always enjoyed. However, this may not be such a powerful draw in today’s more environmentally conscious world.

Since they were first mooted, UK spaceports have experienced resistance from environmental organizations concerned with both the greenhouse-gas emissions regular space launches will produce, and the impact on human health, flora and fauna.

Rockets release pollutants up to about 80 km into the sky, which is so far above the clouds that they are not dispersed by rain. They therefore remain in the atmosphere for two and a half years compared to just a few weeks for pollution closer to the ground

The space industry currently consumes about 1% of fossil fuels burned by conventional aviation. But this figure will rise with the tenfold increase in rocket launches and emissions that is expected in the next 10–20 years. What’s worse, the emissions from launches are more harmful than those from aviation. Rockets release pollutants up to about 80 km into the sky, which is so far above the clouds that they are not dispersed by rain. They therefore remain in the atmosphere for two and a half years compared to just a few weeks for pollution closer to the ground.

Eloise Marais and colleagues from University College London, with collaborators at the University of Cambridge and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), used a 3D model to explore the impact of rocket launches and re-entry (figure 1). They found that soot particles emitted by rockets at current launch rates are already a concern, with their climate effect 400–500 times greater than soot particles released from Earth-bound sources (Earth’s Future 10 e2021EF002612). Another study – led by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and published the same month, June 2022 – used different tools but came to a similar conclusion: soot particles from rocket launches have a significant detrimental impact on climate (JGR Atmospheres 127 e2021JD036373).

“Soot particles are very, very efficient at absorbing the Sun’s rays and warming the atmosphere,” Marais explains. “And all rockets are going to produce nitrogen oxides that can deplete ozone in the ozone layer, and also water vapour, which is not great if we’re releasing it into layers of the atmosphere where it is fairly foreign.”

Compounding the issue are spent stages and decommissioned satellites adding to the growing amount of space junk re-entering Earth’s atmosphere. When space junk burns through the mesosphere it produces yet more nitrogen oxides, as well as a host of different particles that could contribute to ozone depletion.

Marais is quick to point out that the effect on the ozone layer is relatively small, but this may change if the rate of satellite launches continues at its current pace: “We don’t have to have the same amount of emissions coming from rocket launches to have the same climate effect as Earth-bound sources.”

Environmental agenda

There is a strong argument that the benefits of increased satellite launches outweigh the environmental costs. For example, more satellites mean better monitoring of half of the UN’s 54 essential climate variables; democratizing connectivity and Internet access; and allowing for more precise navigation and weather forecasting. But environmental sustainability is still high on the agenda for each of the UK spaceports hoping to launch in 2023.

Spaceport Cornwall’s environmental impact has been a key consideration from the outset. As it operates from an existing airport, it avoids the extra carbon footprint and disturbance to local flora and fauna that comes with building a site from scratch. It is also exclusively a horizontal launch facility, meaning the rockets taking off from there are smaller and produce considerably fewer combustion byproducts than comparable vertical launch rockets. Yet there is still a way to go before the consortium can reach its aim of becoming the world’s first carbon-neutral spaceport by 2030. “We did a whole lifecycle analysis around launch, looking at the good, the bad and the ugly, even before Start Me Up,” says Thorpe. “Now, we’re looking at not just offset or mitigation, but how do we bring that impact down and do it in a more efficient and sustainable way.”

An obvious route to improving sustainability is being explored for launches at SaxaVord and Sutherland, where rocket companies are attempting to replace existing rocket fuels (primarily solid rocket fuel, hydrazine, kerosene and cryogenic/hydrogen fuel) with more environmentally friendly alternatives.

The private rocket company Skyrora – which has agreed a multi-launch deal with the SaxaVord spaceport – uses Ecosene, a premium kerosene derived from unrecyclable plastic waste. The low-temperature catalytic pyrolysis process developed to make Ecosene produces 70% lower CO2 emissions compared to classic methods of fuel production.

Similarly, another launch company Orbex – which plans to launch its Orbex Prime rocket from Space Hub Sutherland – uses the renewable ultralow-carbon fuel BioLPG. This is produced as a byproduct of the waste and residual material from renewable diesel production. A study by the University of Exeter modelled emissions from Orbex Prime, calculating that launches will have a carbon footprint up to 96% lower than those running on fossil-fuel alternatives.

For Marais, though, these fuels miss the mark. They may have a lower carbon impact in their production, but they are still going to release the same pollutants into the higher layers of the atmosphere as traditional fuels. “As well as carbon neutrality, we should also be considering pollution neutrality,” she says. “There should be funding for environmental scientists to look at this further; funding that is independent of the companies that are considering these fuels.”

Impacting the space environment

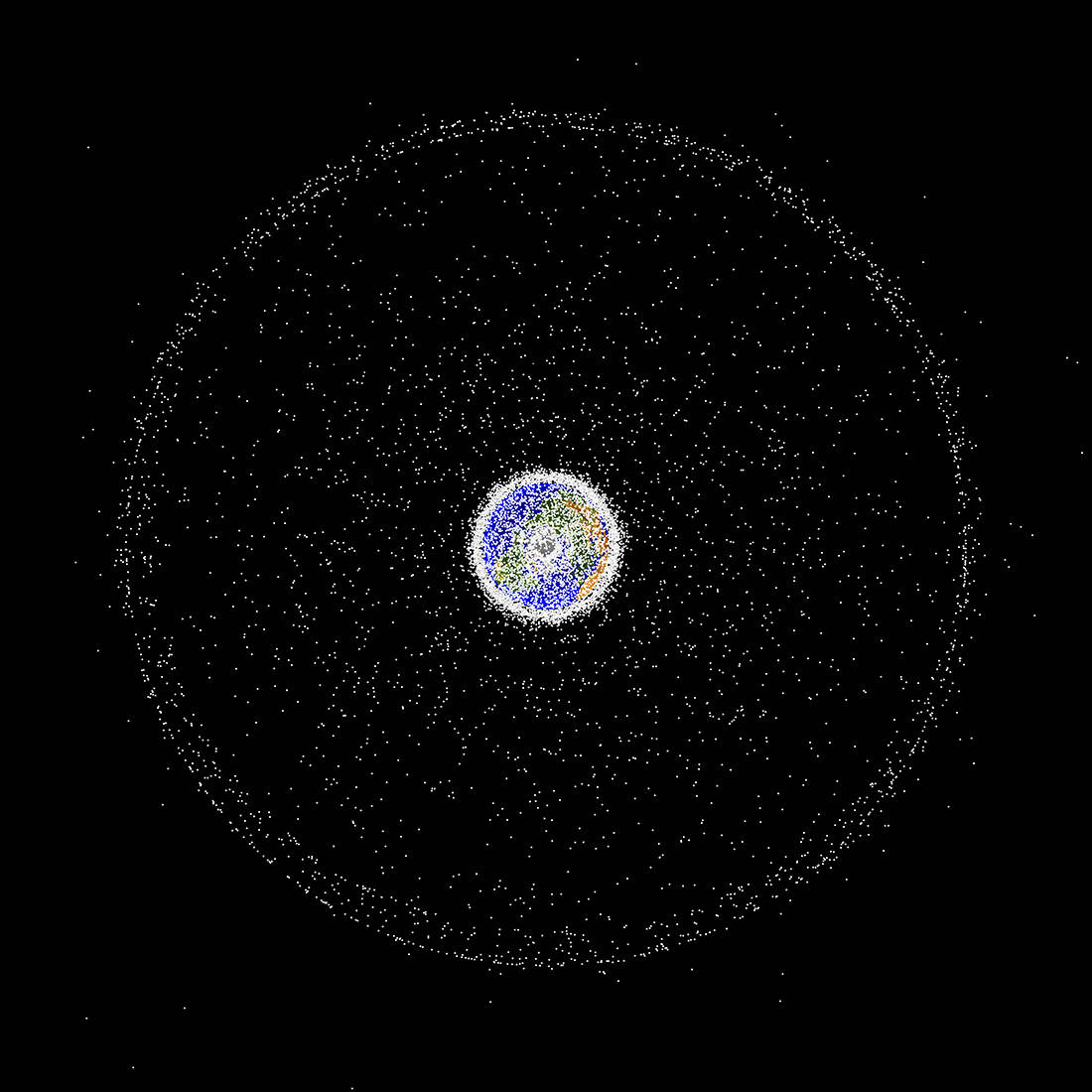

With so many questions about the impact of spaceports on the environment, it can be easy to forget the impact increased satellite launches are having on their final destination: space. There are currently 10,513 satellites orbiting Earth, a number that has more than doubled since 2019 according to the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs.

Connie Walker – a scientist at the US National Science Foundation (NSF)’s NOIRLab who co-leads the International Astronomical Union’s Center for the Protection of the Dark and Quiet Sky – says that there could be anything from 100,000 to 430,000 satellites in orbit within the next decade.

Her chief concern is the impact on astronomy of the large satellite constellations being developed by SpaceX, OneWeb and others. Already, these table-sized satellites (too large to be launched from UK spaceports) are damaging ground-based observations of the night sky. Satellite downlink transmissions can mess up radio observations of, for example, the cosmic microwave background and star formation. And satellites passing through an observatory’s line of sight appear as streaks, which make it challenging to observe transient events, such as gamma ray bursts, or monitor hazardous asteroids for planetary defence.

Recently, the NSF and SpaceX signed an agreement to mitigate the effects of satellites on ground-based astronomy. The agreement involves making SpaceX’s next generation of satellites less bright; reducing radio interference over radio quiet zones by briefly turning off downlink transmissions; and SpaceX opting out of a prior agreement that requires certain observatories to shut off their laser guide stars as satellites pass over. Walker hopes that every satellite developer and operator will follow suit, even start-ups and academic groups building smallsats intended for launch from UK spaceports. “The smallsats are not quite as much of a problem,” she says. “But if we get hundreds and thousands up there, regardless of whether they’re cubesats or something a little bit bigger, it’s going to make a difference – we all have to act as good stewards”.

Annett too is concerned about the space environment becoming cluttered, but for a different reason. Kessler syndrome refers to the hypothetical scenario where space junk collides with satellites or spacecraft, in turn creating more debris resulting in a chain reaction that would make the near-Earth environment unusable for decades.

Currently, over 130 million pieces of space debris – including 36,500 objects larger than 10 cm, from entire satellites to tools dropped by astronauts – are estimated to be orbiting Earth. This figure will only grow with more launches. “We all know about the danger of Kessler syndrome,” Annett says. “But the UK is a leader in the UN’s long-term sustainability goals for space, and we’re investing in UK companies that can help us look after that environment, such as ClearSpace and Astroscale, which are designing missions to remove space debris.”

There is one piece of space debris, circling in low Earth orbit every 90 minutes, that would be particularly satisfying to capture in a UK mission launched from home soil. Prospero is a long-decommissioned scientific test satellite that stands as a memento to the UK’s first and only successful launch of a vehicle into space. It flew aboard the British rocket Black Arrow from the Woomera rocket range in South Australia in 1971. But the feat was never repeated as the UK government at the time deemed the launch business too expensive.

Over 50 years later, a host of different factors – economic benefits, jobs and skills generation, and Earth and space environmental impacts – will go into deciding whether the launch business has become worth pursuing again. And if it has, wouldn’t removing Prospero be a fitting way to celebrate finally creating a successful, sustainable launch industry?

- On 4 April 2023, Virgin Orbit filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in the US after failing to secure new investment. The filing means that the business can continue operating and address its financial issues, but is protected against creditors. On 16 March 2023, Virgin Orbit had paused operations and furloughed staff while the company sought a new investment plan.