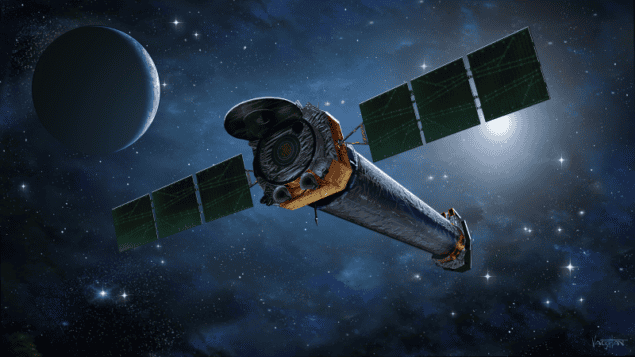

X-ray astronomers in the US have begun a campaign to save the Chandra X-ray Observatory from budget cuts that would effectively end the mission. They assert that the craft, which was launched in 1999, has plenty of life left in it. Cancelling support could, they say, damage scientific efforts to understand the universe and the careers of an emerging generation of X-ray astronomers.

Like other government agencies, NASA is facing financial restrictions. Although US president Joe Biden’s budget request for financial year (FY) 2025, which starts on 1 October, aims to increase funding for most science agencies, much of the proposed increase merely compensates in part for cuts this year over FY2023 levels.

While the president’s budget request is always more of a wish list than a forecast of actual numbers, the figures in each agency’s requests can indicate its leaders’ priorities – and for NASA that includes no funding for Chandra. In its budget request, NASA claimed that the craft “has been degrading over its mission lifetime to the extent that several systems require active management…increasing management costs beyond what NASA can afford” – an observation that surprised researchers.

Mark Clampin, NASA’s director of astrophysics, says that it is currently a “challenging budget environment”, which means making “difficult decisions”. But he insists the budget request is “not a cancellation of Chandra” and that NASA will hold a “mini-senior review” to seek community guidance options for reducing the cost of science operations for both the Hubble Space Observatory and Chandra. “Once we have received recommendations from that review,” Clampin says, “we will determine a path forward for Chandra and Hubble.”

‘Shocked and appalled’

While astronomers had expected funding difficulties for Chandra in the FY2025 proposal, no-one imagined that it would mean an “orderly mission drawdown to minimal operations”. David Pooley – an astronomer at Trinity University in San Atonio, Texas – told Physics World that he is “shocked and appalled” by the decision. “Other branches of astronomy can go elsewhere, like the National Science Foundation, for funds. But astrophysics in the US is 100% dependent on NASA.” ‘Great observatories’ – the next generation of NASA’s space telescopes, and their impact on the next century of observational astronomy

Chandra’s supporters say the craft has much more to offer. “Some thermal issues were patched, so that users don’t notice any problem,” says Laura Lopez, an astronomer from Ohio State University. She admits that some build-up of contaminants on the observatory’s charge-coupled device has required longer observing time, but claims “there are no additional challenges”.

Scientists have now created a grassroots organization, Save Chandra, to generate support for the observatory. “I’ve been rallying scientists to sign a letter asking for the restoration of funds for users,” says Pooley. “Later, we’ll look for more organized efforts.”

So far, the organizers recommend that astronomers reach out to their representatives and senators. Given that Congress is unlikely to agree on the final FY2025 budget for several months and Congressional committees have been known to alter even small items in the budget proposals of agencies such as NASA, both time and politics may be on their side.

For the scientific community, however, the challenge is not only keeping Chandra funded but also saving the careers of a generation of PhD and postdoc X-ray astronomers. According to Lopez, grants from Chandra support several of her PhD students – and losing that support would force them to become teaching assistants rather than research assistants. Other astronomical disciplines could also suffer as they rely on Chandra for follow-up studies.