Effective management training can equip scientists and engineers with powerful tools to boost the impact of their work, identify opportunities for innovation, and build high-performing teams

Most scientific learning is focused on gaining knowledge, both to understand fundamental concepts and to master the intricacies of experimental tools and techniques. But even the most qualified scientists and engineers need other skills to build a successful career, whether they choose to continue in academia, pursue different pathways in the industrial sector, or exploit their technical prowess to create a new commercial enterprise.

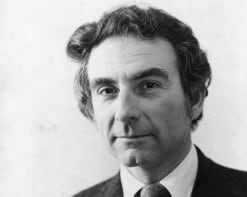

“Scientists and engineers can really benefit from devoting just a small amount of time, in the broad scope of their overall professional development, to understanding and implementing some of the ideas from management science,” says Peter Hirst, who originally trained as a physicist at the University of St Andrews in the UK and now leads the executive education programme at MIT’s Sloan School of Management. “Whether you’re running a lab with just a few post-docs, or you have a leadership role in a large organization, a few simple tools can help to drive innovation and creativity while also making your team more effective and efficient.”

MIT Sloan Executive Education, part of the management school, the business school of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, US, offers more than 100 short courses and programmes covering all aspects of business innovation, personal skills development, and organizational management, many of which can be accessed in different online formats. Delivered by expert faculty who can share their experiences and insights from their own research work, they are designed to introduce frameworks and tools that enable participants to apply key concepts from management science to real-world situations.

Research groups are really a type of enterprise, with people working together to produce clearly defined outputs

Peter Hirst, MIT Sloan School of Management

One obvious example is the process of transforming a novel lab-based technology into a compelling commercial proposition. “Lots of scientists develop intellectual property during their research work, but may not be aware of the opportunities for commercialization,” says Hirst. “Even here at MIT, which is known for its culture of innovation, many researchers don’t realize that educational support is available to help them to understand what’s needed to transfer a new technology into a viable product, or even to become more aware of what might be possible.”

For academic researchers who want to remain focused on the science, Hirst believes that management tools originally developed in the business sector can offer valuable support to help build more effective teams and nurture the talents of diverse individuals. “Research groups are really a type of enterprise, with people working together to produce clearly defined outputs,” he says. “When I was working as a scientist, I really didn’t really think about the human system that was doing that work, but that’s a really important dimension that can contribute to the success or failure of the whole enterprise.”

Modern science also depends on forging successful collaborations between research groups, or between academia and industry, while researchers are under mounting pressure to demonstrate the impact of their work – whether for scientific progress or commercial benefit. “Even if you’re working in academia, it’s really important to understand the contribution that your work is making to the whole value chain,” Hirst comments. “It provides context that helps to guide the work, but it’s also vital for sustainably securing the resources that are needed to pursue the science.”

The training offered by MIT Sloan takes different formats, including short courses and longer programmes that take a deeper dive into key topics. In each case, however, the faculty designs tasks, simulations and projects that allow participants to gain a deeper understanding of key concepts and how they might be exploited in their own workplace. “People believe by seeing, but they learn by doing,” says Hirst. “Our guiding philosophy is that the learning is always more effective if it can be done in the context of real work, real problems, and real challenges.”

Many of the courses are taught on the MIT campus, offering the opportunity for delegates to discuss key ideas, work together on training tasks, and network with people who have different backgrounds and experience. For those unable to attend in person, the same ethos extends to the two types of online training available through the executive education programme. One stream, developed in response to the Covid pandemic, offers live tutoring through the Zoom platform, while the other provides access to pre-recorded digital programmes that participants complete within a set time window. Some of these self-paced courses adopt a sprint format inspired by the concepts of agile product development, enabling participants to break down a complex challenge or opportunity into a series of smaller questions that can be tackled to reach a more effective solution.

“It’s not just sitting and watching, people really have the opportunity to work with the material and apply what they are learning,” explains Hirst. “In each case we have worked hard with the faculty to figure out how to achieve the same outcomes through a different type of experience, and it’s been great to see how compelling that can be.”

Evidence that the approach is working can be found in the retention rate for the self-paced courses, with more than 90% of participants completing all the modules and assignments. The Zoom-based programmes also remain popular amid the more general post-pandemic return to in-person training, providing greater flexibility for learners in different parts of the world. “We have tried to find the sweet spot between effectiveness and accessibility, and many people who can’t come to campus have told us they find these courses valuable and impactful,” says Hirst. “We have put the choice in the hands of the learners.”

Plenty of scientists and engineers have already taken the opportunity to develop their management capabilities through the courses offered by MIT Sloan, particularly those that have been thrown into leadership positions within a rapidly growing organization. “Perhaps because we’re at MIT, we are already seeing scientists and engineers who recognize the value of engaging with ideas and tools that some people might dismiss as corporate nonsense,” says Hirst. “Generally speaking, they have really great experiences and discover new approaches that they can use in their labs and businesses to improve their own work and that of their teams and organizations.”

For those who may not yet be ready to make the leap into developing their personal management style, Hirst advocates courses that analyse the dynamics of an organization – whether it’s a start-up company, a manufacturing business or a research collaboration. The central idea here is to apply concepts from systems engineering to organizations, and how work gets done by a human system, to improve overall productivity and performance.

One case study that Hirst cites from the biomedical sector is the Broad Institute, a research organization with links to MIT and Harvard that has developed a platform for generating human genomic information. “Originally they were taking months to extract the genomic data from a sample, but they have reduced that to a week by implementing some fairly simple ideas to manage their operational processes,” he says. “It’s a great example of a scientific organization that has used systems-based thinking to transform their business.”

Others may benefit from courses that focus on technology development and product strategy, or an entrepreneurship development programme that immerses participants in the process of creating a successful business from a novel idea or technology. “That programme can be transformational for many people,” Hirst observes. “Most people who come into it with a background in science and engineering are focused on demonstrating the technical superiority of their solution, but one of the big lessons is the importance of understanding the needs of the customer and the value they would derive from implementing the technology.”

For those who are keen to develop their skills in one particular area, MIT Sloan also offers a series of Executive Certificates that enable learners to choose four complementary courses focusing on topics such as strategy and innovation, or technology and operations. Once all four courses in the track have been completed – which can be achieved in just a few weeks as well as over several months or years – participants are awarded an Executive Certificate to demonstrate the commitment they have made to their own personal development.

More information can be found in a digital brochure that provides details all of the courses available through MIT Sloan, while the website for the executive education programme provides an easy way to search for relevant courses and programmes. Hirst also recommends reading the feedback and reviews from previous participants, which appear alongside each course description on the website. “Prospective learners find it really useful to see how people in similar situations, or with similar needs, have described their experience.”